Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Full description not available

M**S

Both entertaining and insightful.

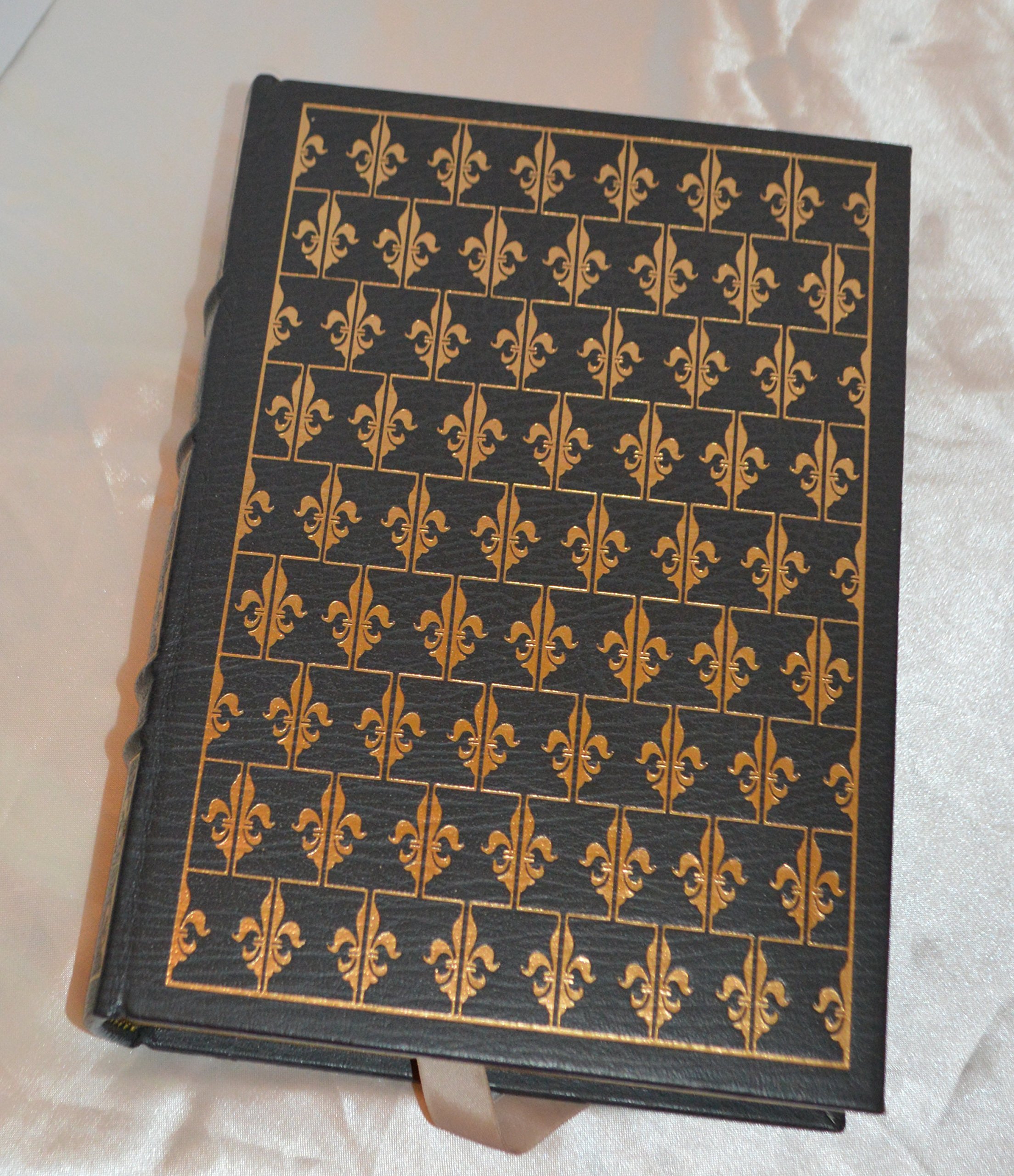

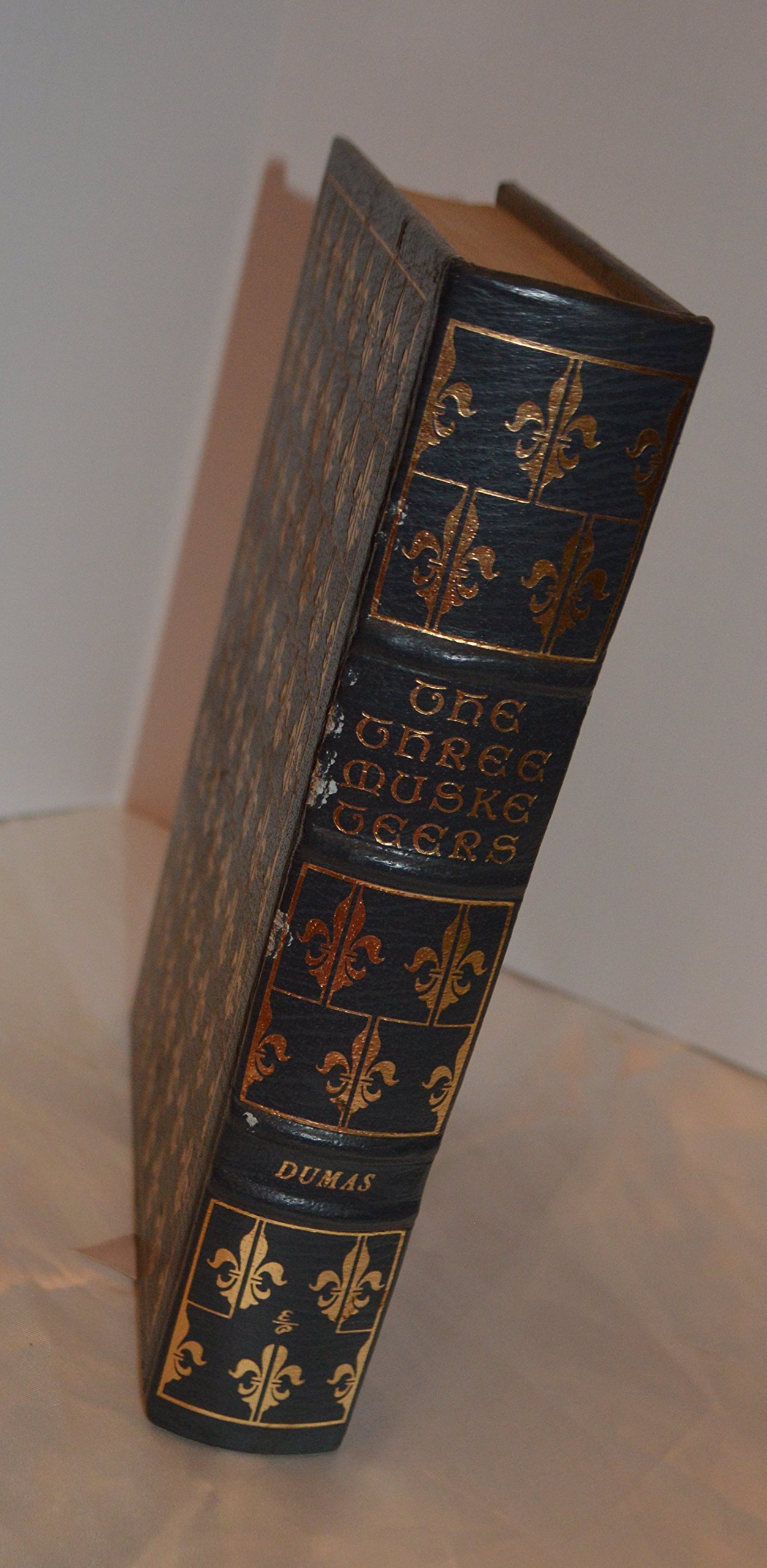

All translators must struggle with two competing goals: 1) being faithful to the original author and 2) making the translated text accessible to the reader. In this translation of _The Three Musketeers_, the translator, Richard Pevear, generally gravitates towards the first goal. His vocabulary choices almost always favor the original French usage rather than modern English usage. For example, early in the book, Pevear refers to Milady as Rochefort's "interlocutrix". Now I don't know about you, but I grew up going to California public schools, and if I ever used a word like "interlocutrix", I'd get my face bashed into a locker. My background notwithstanding, I think it's clear what's going on here. The word "interlocutrix" is an uncommon yet legitimate English word with French roots. Pevear has chosen to use the uncommon word in order to remain faithful to Dumas' original French text which presumably used the French cognate for "interlocutrix" whatever that is.I could come up with literally dozens of such examples, and eventually I just started keeping a separate list of obscure words and definitions so I only needed to refer to a short list rather than slog through the dictionary every time I came upon one of those recurring obscure words. By the time I finished the book, I had a five page (12 pt. Times New Roman type, single-spaced) list of obscure words. They range from 17th century French clothing ("tabard", "doublet", "jerkin") to horse-related terminology ("caparison", "sorrel", "croup") to 17th century military terminology ("counterscarp", "revetments", "circumvallation") and many others. In all these cases, I'm convinced that Pevear chose to use the English cognates of original French words rather than more modern English equivalents.In fairness to Pevear, he does provide extensive notes explaining the historical references made by Dumas, which is extremely reader-friendly, and I profited from them greatly. Even in these notes, however, he leaves out some obvious choices such as "Rosinante" and "Circe".In short, if you're an English speaker with no knowledge of French but would like to get a feel for Dumas' prose style and usage, this is the book for you. It is a remarkably faithful translation that really gives you a feel for the nuances of the original text. If you're unfamiliar with the obscure words chosen for the translation but are willing to make repeated trips to the dictionary (or keep a side list as I did), you'll be richly rewarded with keener understanding of life in 17th century France as well as a greater appreciation of Dumas' prose style.For what it's worth, a doublet is close fitting jacket worn by European men in the 16th and 17th centuries; a jerken is a hip-length collarless and sleeveless jacket worn over a doublet, and a tabard is a tunic or cape-like garment emblazoned with a coat of arms. A caparison is an ornamental covering for a horse or for its saddle or harness; a sorrel is a brownish-orange colored horse, and a croup is the rump of a beast of burden, especially a horse. A counterscarp is the outer side of a ditch used in fortifications; revetments is a barricade against explosives, and circumvallation is the act of surrounding with a rampart. Rosinante is the name of Don Quixote's horse, and Circe is the goddess of Greek mythology who turned Odysseus's men temporarily into pigs but later gave him directions for their journey home. And an interlocutrix is simply a woman who is participating in a conversation.I'll close with my favorite quote from the book, spoken by Cardinal Richelieu. He was musing about finding someone to assassinate the Duke of Buckingham, but Milady argued that potential assassins would be afraid to proceed for fear of "torture and death". Le Cardinal replied, "In all times and in all countries, especially if those countries are divided by religion, there will always be fanatics who ask for nothing better than to be made martyrs." It's as true today as it was when Dumas' wrote it more than 160 years ago.

M**L

Terrific story, terrific pace!

The last Dumas I read was The Count of Monte Cristo, back in 2003 or so. I remember it having some long patches, some filler-material, but I also remember being enthralled by the sheer storytelling power, and finishing it in record time.The Three Musketeers, I think, is better still. There's very little padding, and the only bit that rankled a little was a section in which the exposition was handled very stagily, in the sense of old-fashioned exposition: two nonentities come onto the stage and explain all the backstory in dialogue that is as flat as a pancake. In the section in question, however, the two characters were important ones, and it seemed odd how they suddenly began to behave. It was around this section too that D'Artagnan started behaving rather strangely, more like a puppet than a man. Not only was he using one woman to get at another, (Kitty, Milady's maid, to get at Milady) and showing uncharacteristic integrity, but his apparent bedazzlement by Milady was somehow unbelievable.Apart from that, the story zips along at such a pace that you find yourself reading page after page, trying to keep up with the speed of things. The humour is wonderful, there's very little purple prose for a 19th century novel, and the characters, though occasionally inconsistent, are in general well-drawn. The villains are villains to the core; no mistaking them. The heroes will die for anything and everything that seems true. The women are wonderful, and the men passionate and energetic. And the suspense is terrific (even if you've seen one or two movie versions of the story).Certainly the morals of the the characters leave something to be desired. Dumas even comments on their behaviour a couple of times by telling us that this was how people behaved then - as if to excuse the fact that he was making them behave this way. And the way he weaves history into his story - bending it when necessary - is excellent.

Trustpilot

5 days ago

2 months ago