معلومات عنا

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 Desertcart Holdings Limited

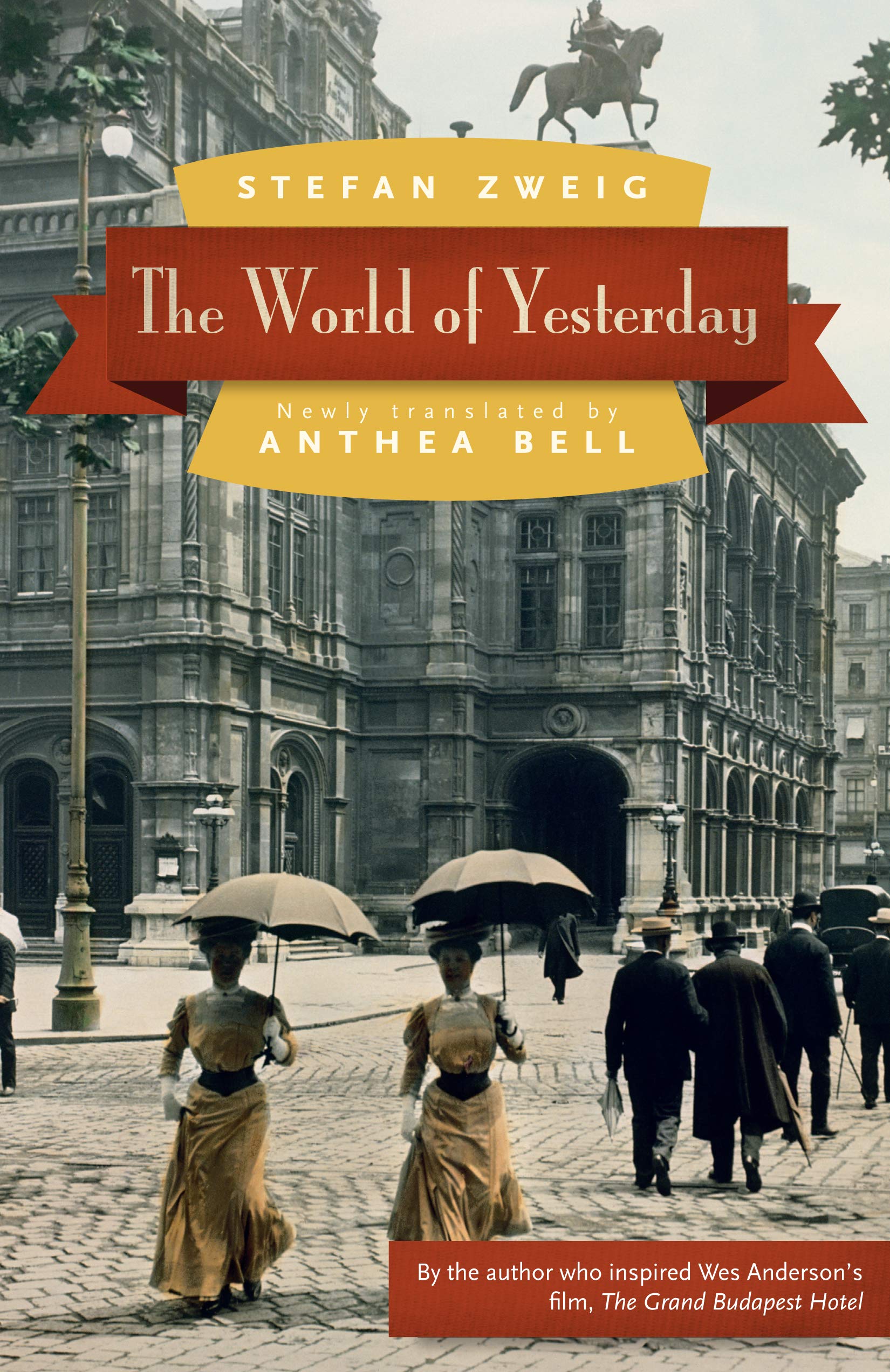

The World of Yesterday [Zweig, Stefan, Bell, Anthea] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. The World of Yesterday Review: Thank you, Herr Zweig! - This is a wonderful, heartbreaking memoir of, first, Vienna before WWI from the viewpoint of a child; then all of literary Europe between the two world wars from the viewpoint of an increasingly successful writer, and finally of a stateless man in England, witnessing the irrepressible forces of the second world war about to overtake everything. During his adulthood, he also visited Russia, India, Argentina, Brazil, and the US, all largely for literary purposes. Two parts I thought were a bit unintentionally funny: early on he goes on at length about how healthy it was for the sexes to have more freedom to commingle, and he states that when young men and women were kept so separate, and sex was so forbidden outside of marriage, pornography was a terrible problem, debasing both sexes. Well, I'm afraid that the increased commingling of the sexes didn't exactly reduce that particular problem... And again, there was a part where he really goes on and on talking about how one of the main reasons his writing was so successful was that he loved to edit out unnecessary or redundant parts of his initial drafts. But that very section of his book is incredibly repetitive! :) And indeed, several sections are -- as if he couldn't resist coming up with yet one more way of saying the exact same thing. However - I wouldn't let this stop anyone from reading the book. It's delightfully written, and it's about such an important period of time in European history. He had intellectual/literary relationships with many important people, from Strauss to Freud, and if for those recollections alone, the memoir is quite valuable. Review: Farewell Vienna - Hello Mr. Trump - A Trip Through Time and Back - This is the pre-suicide autobiography of accomplished Viennese writer Stefan Zweig, who lived through the final dissolution of the old Austrian Hapsburg dynasty and ended his life in 1943 before the end of WWII. The original was written in German, which must have been exceedingly difficult to translate adequately, given its complex thought-streams and complicated sentence structure. So first off, an admiring nod to the translator, Anthea Bell, who did a masterful job of conveying the heart and soul of this book to readers of the English language and supplying excellent background in her translator's note which opens the book. Zweig was a man of many faces -- brilliant, yes! and also exceptionally self-aware. The book opens with a fascinating account of his Jewish boyhood in Vienna, his early training in the rigorous and pedantic German schools, and builds to a climax as he reflects on his experiences as a disenfranchised member of the Jewish artistic community during and after the Nazi take-over in Germany and Austria. He was conscious of the deep changes that were undermining the old regime in his native Austria and in Europe, particularly the rise of fascist sympathizers in many places in Europe during his lifetime. The tension was palpable in his haunting descriptions of life on the edge of communal insanity as the Hitler machinery marched through Europe in the late 1930’s and struck down one basic human freedom after another. It was an insidious and covert operation that became obvious to most only after-the-fact. All his books were ultimately banned by the Nazis and he fled the country and lived in exile for several years. He seems to have largely discounted his ultimate success as a major contributor to the historical record of his day while he was living through the process, chagrined that he could do nothing about it except to experience it deeply and shoulder his burden as a super-sensitive soul. In many ways, as I read through this rich and elegant exploration of his life and times in Vienna, Paris, Italy and America, I quietly sympathized with him at the loss of his beloved country to war and hate. I can almost hear his stark voice commenting here that he was much more rooted in literature and philosophy than he was in routine daily life, and that he expected his artistic and scholarly efforts, small as he may have viewed them, to affect or change the course of world history for the better. He had maximum refinement but lacked the common touch at a time when common people were rising and trying to upend the old regime in Austria and in so doing, opening themselves to the Nazi take-over. In light of his imminent suicide shortly after completing this book, it is fair to assume that he felt adrift on this planet as a writer who could no longer grasp what went so terribly wrong all at once -- or how to amend it with all his worldly knowledge and massive literary skills. The realization that his past conditioning was no longer sufficient to sustain him must have been personally wrenching. In his mind, a new day was coming unbidden, and with it a profound shift in mores. In my own life, with the ascent of Trumpism and its blatant disregard for human rights, it felt like deja vu to absorb this book, which is not only a shout-out to our collective past as scholars and thinkers, writers, musicians and artists of the sort who were at home in pre- WWI Vienna, but also a potent reminder that a shift in culture can be ruthless and insane before the “new normal” becomes apparent. It is both a swan song and a warning – and that is primarily why our book club chose to experience this book together. As a sympathetic portrait of a man and a world in acute distress, it is helpful to read it while trying to live through the crude and unconscious political agendas of our own times. It sparked intense debates and fruitful discussion among our group. Take some time to read through it slowly and let it sink in -- it is a complex book of many layers and uncannily prescient.

| Best Sellers Rank | #32,131 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #69 in Author Biographies #106 in Historical European Biographies (Books) #825 in Memoirs (Books) |

| Customer Reviews | 4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars (1,774) |

| Dimensions | 5.5 x 1.25 x 8.5 inches |

| Edition | Reprint |

| ISBN-10 | 0803226616 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0803226616 |

| Item Weight | 1.24 pounds |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 472 pages |

| Publication date | May 1, 2013 |

| Publisher | University of Nebraska Press |

B**E

Thank you, Herr Zweig!

This is a wonderful, heartbreaking memoir of, first, Vienna before WWI from the viewpoint of a child; then all of literary Europe between the two world wars from the viewpoint of an increasingly successful writer, and finally of a stateless man in England, witnessing the irrepressible forces of the second world war about to overtake everything. During his adulthood, he also visited Russia, India, Argentina, Brazil, and the US, all largely for literary purposes. Two parts I thought were a bit unintentionally funny: early on he goes on at length about how healthy it was for the sexes to have more freedom to commingle, and he states that when young men and women were kept so separate, and sex was so forbidden outside of marriage, pornography was a terrible problem, debasing both sexes. Well, I'm afraid that the increased commingling of the sexes didn't exactly reduce that particular problem... And again, there was a part where he really goes on and on talking about how one of the main reasons his writing was so successful was that he loved to edit out unnecessary or redundant parts of his initial drafts. But that very section of his book is incredibly repetitive! :) And indeed, several sections are -- as if he couldn't resist coming up with yet one more way of saying the exact same thing. However - I wouldn't let this stop anyone from reading the book. It's delightfully written, and it's about such an important period of time in European history. He had intellectual/literary relationships with many important people, from Strauss to Freud, and if for those recollections alone, the memoir is quite valuable.

A**A

Farewell Vienna - Hello Mr. Trump - A Trip Through Time and Back

This is the pre-suicide autobiography of accomplished Viennese writer Stefan Zweig, who lived through the final dissolution of the old Austrian Hapsburg dynasty and ended his life in 1943 before the end of WWII. The original was written in German, which must have been exceedingly difficult to translate adequately, given its complex thought-streams and complicated sentence structure. So first off, an admiring nod to the translator, Anthea Bell, who did a masterful job of conveying the heart and soul of this book to readers of the English language and supplying excellent background in her translator's note which opens the book. Zweig was a man of many faces -- brilliant, yes! and also exceptionally self-aware. The book opens with a fascinating account of his Jewish boyhood in Vienna, his early training in the rigorous and pedantic German schools, and builds to a climax as he reflects on his experiences as a disenfranchised member of the Jewish artistic community during and after the Nazi take-over in Germany and Austria. He was conscious of the deep changes that were undermining the old regime in his native Austria and in Europe, particularly the rise of fascist sympathizers in many places in Europe during his lifetime. The tension was palpable in his haunting descriptions of life on the edge of communal insanity as the Hitler machinery marched through Europe in the late 1930’s and struck down one basic human freedom after another. It was an insidious and covert operation that became obvious to most only after-the-fact. All his books were ultimately banned by the Nazis and he fled the country and lived in exile for several years. He seems to have largely discounted his ultimate success as a major contributor to the historical record of his day while he was living through the process, chagrined that he could do nothing about it except to experience it deeply and shoulder his burden as a super-sensitive soul. In many ways, as I read through this rich and elegant exploration of his life and times in Vienna, Paris, Italy and America, I quietly sympathized with him at the loss of his beloved country to war and hate. I can almost hear his stark voice commenting here that he was much more rooted in literature and philosophy than he was in routine daily life, and that he expected his artistic and scholarly efforts, small as he may have viewed them, to affect or change the course of world history for the better. He had maximum refinement but lacked the common touch at a time when common people were rising and trying to upend the old regime in Austria and in so doing, opening themselves to the Nazi take-over. In light of his imminent suicide shortly after completing this book, it is fair to assume that he felt adrift on this planet as a writer who could no longer grasp what went so terribly wrong all at once -- or how to amend it with all his worldly knowledge and massive literary skills. The realization that his past conditioning was no longer sufficient to sustain him must have been personally wrenching. In his mind, a new day was coming unbidden, and with it a profound shift in mores. In my own life, with the ascent of Trumpism and its blatant disregard for human rights, it felt like deja vu to absorb this book, which is not only a shout-out to our collective past as scholars and thinkers, writers, musicians and artists of the sort who were at home in pre- WWI Vienna, but also a potent reminder that a shift in culture can be ruthless and insane before the “new normal” becomes apparent. It is both a swan song and a warning – and that is primarily why our book club chose to experience this book together. As a sympathetic portrait of a man and a world in acute distress, it is helpful to read it while trying to live through the crude and unconscious political agendas of our own times. It sparked intense debates and fruitful discussion among our group. Take some time to read through it slowly and let it sink in -- it is a complex book of many layers and uncannily prescient.

E**D

Beautiful Memoir of a Beautiful Time, Tinged With Tragedy

I must admit that I had only heard of Stefan Zwieg, one of the most important writers of his time, from Rod Dreher’s blog, in context of Zwieg’s memoir capturing the grandeur of Europe pre-Great War, the socioeconomic chaos endured by the losers of that conflict, and the lead up to WWII. The book was published in 1942, the year Zweig and his second wife committed suicide in Brazil, by then nationless and stripped of nearly everything. Although these conflicts are foreshadowed throughout the book, it’s about so much more than that. It’s about European civilization at its heights. Any romantic who imagines sitting in Parisian literary salons, listening to opera in Vienna, or meeting great artists in their turn of the century studios will love this book. It’s filled with many slice of life observations about the mores and manners of people living in that time and place. The list of famous writers, poets, musicians and artists Zwieg rubbed elbows with throughout Austria, Switzerland, Italy, France and England is incredible, a who’s who of the time. Ravel, Toscanini, Rodin, Dali, HG Wells, Freud, Thomas Mann, Theodor Herzl, Richard Strauss, Shaw - this list goes on and on - were his peers, friends and acquaintances. This is a lovely book written by a seemingly lovely man devoted to art and culture and most of all, Europe, which one reads with a constant sense of foreboding, given the two calamities which befell the Continent. Barbara Tuchman’s “Proud Tower” is a masterpiece of history if you wish to learn about the socioeconomic conditions which roiled the Belle Epoch. But if one wants a slice of life, an insight into how so many great artists of the time lived and thought, this book is a must-read.

M**D

Fantastic and very moving account of a critical time and place in history. Makes me fear that this time isn’t different and that history unfortunately does in fact repeat….

J**N

I’ve read and greatly enjoyed a couple of Zweig’s novels and, following Clive James' recommendation in an article about Zweig, bought this to take along on a trip to Vienna (which is where he was born in 1881). Zweig, who was one of the most popular and translated writers in the world during the 1920s and 30s, began writing this memoir in 1934 when he left Austria (first for England, later for Brazil) in anticipation of the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938. He completed it in Brazil in 1942 and posted the manuscript to his publisher the day before he and his wife committed suicide. The book contains his memories of his life, written - as he points out in his preface - without access to notes, his books or letters from friends: "I have nothing left of my past, then, but what I carry in my head" [p22]. He remembers how the Austrians lived well "with light hearts and minds at ease in old Vienna, and the Germans in the north looked down with some annoyance and scorn at us, their neighbours on the Danube" because they didn't observe "strict principles of order" but instead indulged themselves, "ate well, enjoyed parties and the theatre" [p45]. He describes vividly how he and his schoolfriends immersed themselves in everything that was new in the theatre, literature and art - ignoring the (as they saw it) outmoded writers being taught in their classes in favour of books by new authors like Rilke, Strindberg and Nietzsche which they tracked down assiduously (he tells how he astonished Paul Valery by describing how they'd found and admired his first poems in a small literary journal, eighteen years before they were published in 1916). This enthusiasm for literature stayed with him all his life, and he describes meeting with authors like Rilke, Hofmannsthal and Rolland (I was so engrossed in his story that I kept resorting to Wikipedia to look up many of the names of which I'd never heard - indeed, Zweig notes on p142 that many established critics confuse Verhaeren with Verlaine, "just as they got Rolland mixed up with Rostand"). He says that "Rilke never let anything that was less than perfect leave his hands" and that, after a conversation with him, "you were incapable of any kind of vulgarity for hours, even days" [p165]. Other memorable observations include fashions for women ("It is no legend or exaggeration to say that when women died in old age, their bodies had sometimes never been seen, not even their shoulders or their knees, by anyone except the midwife, their husbands, and the woman who came to lay out the corpse" [p96]), and the observation of Friedrich Hebbel ("Sometimes we have no wine, sometimes we have no goblet") in his discussion about the tension between morality and the state in terms of an individual's freedom [p111]. There's an exact and moving description of the moment when his first essay was accepted for publication in the Neue Freie Presse (like "Napoleon presenting a young sergeant with the cross of the Legion d'Honneur on the battlefield" [p128]) by the editor, Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist organization. Later, when he visits the USA on p212, he describes the country's "wonderful freedom", with no questions about his nationality, religion or origin (he had travelled without a passport). Zweig's theme in this book is remembrance of Europe before WWII, which he views as a golden age, recalling "happy hours [...] sitting on the terrace [of his house on the Kapuzinerberg in Salzberg] and looking out at the beautiful and peaceful landscape, never guessing that directly opposite, on the mountain in Berchtesgaden, a man lived who would destroy it all" [p371]. He contrasts the contempt and mistrust which people felt for their governments in 1939 with the attitudes prior to WWI (which were "childishly naïve and gullible" [p247]) - including doctors who "sang the praises of their new prosthetic limbs so eloquently that you almost felt like having a healthy leg amputated, so as to get it replaced by an artificial limb" [p232]. Going further, he describes the work of his friend Ernst Lissauer who, upon the outbreak of WWI, vented his belief that Britain was to blame in a poem called "Hymn of Hate For England" (Lissauer also coined the slogan "Gott strafe England", or "May God Punish England" - which is the origin of the term "strafing", or attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft). Regarding the man who would destroy it all, the way the Nazis came into power - secretly at first, then suddenly - is discussed in the latter part of the book. Zweig says that, with "their unscrupulous methods of deception [they] took care not to show how radical its aims were until the world was inured to them [...] one dose at a time, with a short pause after administering it [...] gradually sounding out opinion and then putting more and more pressure on" [p390]. The description of this technique unfortunately still rings bells today, as governments (and/or would-be dictators) push forward reforms or challenges gradually, beginning with lies and incitement of hatred, until their citizens are one day surprised by how far (and in what direction) their country has travelled. Zweig explicitly describes the feelings of "it can't happen here", or "this can't last long" among his friends, identifying them as "delusion, arising from the same propensity for self-deception" [p403], and showing how it ended in "public infliction of pain, psychological torture and all the refinements of humiliation", with Hitler succeeding in "deadening every idea of what is just and right by the constant attrition of excess" [p432]. An extraordinary book: beautifully written, fascinating and moving. Highly recommended.

E**N

É a história de um mundo que morreu. Um mundo de estabilidade. Um mundo que acreditava do Estado e no Imperador. Que inflação era uma coisa inexistente. No qual os pais determinavam a carreira dos filhos assim que eles nasciam. É claro que isso é um pouco distópico, mas uma distopia diferente da que vivemos atualmente. Vale a pena conferir.

A**L

El mundo de ayer ha sido, y sigue siendo, mi libro estrella. Stefan Zweig vuelca su alma en cada palabra, logrando transportarte a la Europa de principios del siglo pasado y a la vez invitarte a cuestionar el status quo de nuestro propio zeitgeist. Lo leí hace décadas y recientemente he vuelto a hacerlo. Con los años, he descubierto matices que antes se me escapaban. Desde entonces, no he dejado de recomendar esta obra a mis amistades. No te pierdas El mundo de ayer: es imposible ver el mundo igual después de leerlo.

S**R

Good read. Very differently presents the history of Europe during world wars. Kept me engaged through out. Highly recommend for anyone wanting to understand people's state during world wars

ترست بايلوت

منذ 4 أيام

منذ 3 أسابيع